Reflection on the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation

31/10/2017 | By: John Oakes

John Oakes

![Teachers' Corner BerkLOGO.jpeg [360x360] [288x288].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/533bf1b0e4b073f6c7fc73e1/1508840861966-DP3ID7YPQA9MQ2N24C6G/ke17ZwdGBToddI8pDm48kLR91wanN1DY-mWerraBVdJZw-zPPgdn4jUwVcJE1ZvWhcwhEtWJXoshNdA9f1qD7Xj1nVWs2aaTtWBneO2WM-vd-r6kCRDLSj_w7d7aW8FcHiZzlwlc7V1dEcULr6yQyA/Teachers%27+Corner+BerkLOGO.jpeg+%5B360x360%5D+%5B288x288%5D.jpg)

There is much interest in the Christian world on the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation Movement. Even in mostly-atheist Germany, awareness of the history of this world-changing set of events is high. October 31, 1517, is the day when Martin Luther posted his famous 95 theses on the cathedral door in Wittenberg—the starting gun for the Reformation.

What exactly is the Protestant Reformation? What is its legacy, both positive and negative? Are we, as Bible-believing and Bible-obeying Christians, Protestants? Perhaps most importantly, what practical lessons can we learn from the momentous events which in many ways led to the modern world?

First of all, we should introduce ourselves to the great heroes of the Reformation. The big three are Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli and John Calvin. And of course, there are many lesser heroes as well. Luther, Zwingli and Calvin are all complicated men, with incredible strengths, but also with fatal flaws in their character. Are they heroes of Christianity? By almost any measure the answer is yes. All three showed remarkable physical courage and gave up nearly everything in order to pave the way so that we can worship God according to our conscience, with the Bible as our only standard of faith and truth.

Martin Luther

Luther was a man of miraculous resolve. His zeal was for Jesus and for his church. In the face of almost certain death at the hands of the Catholic Church and the Catholic princes, he began a reform in Wittenberg which overturned centuries of dominance over Christendom by Rome and the pope. He created the first translation of the entire Bible into his native German, returning the scriptures to the people. He abolished the most egregious Catholic practices such as indulgences, the system of penances, Roman sacramentalism and reliance on works-based salvation. His discovery from the Book of Romans that salvation is by faith marked one of the greatest turning points in the history of the faith. Yet, his reform did not return Christianity to its biblical roots. His faith-alone doctrine caused him to reject the book of James, which teaches that faith without deeds is dead. His theology was that of the fifth-century theologian Augustine. He maintained a strict church-state structure. Ironically, Luther continued the practice of infant baptism, despite the obvious fact that infants cannot have faith. The Catholic Church, under the influence of 13th century theologian Thomas Aquinas, taught a fairly healthy balance between the sovereignty of God and free will on our part. Luther reversed this to a strict predestination, as taught by Augustine. One can argue that although Luther made fantastic strides in restoring Christian practice, he moved theology in the wrong direction.

Ulrich Zwingli

Most of those whom we would call Protestants actually trace their theology and practice to the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli and the French theologian John Calvin. The two brought about a more radical and thorough reformation than that of Luther. Theirs is known as reformed theology. Most evangelicals are of a Reformed rather than a Lutheran faith. Zwingli headed a church/state in Zurich, Switzerland. He went beyond Luther in removing vestiges of unbiblical practice. Zwinglian worship services have been called, “four walls and a sermon.” Like Luther, he restored the Bible to the common people. Yet his Augustinian predestination was even more thorough than that of Luther. He declared that those who are predestined by God to hell give glory to God equally with those predestined to heaven. Wanting to maintain infant baptism as a means to establish citizenship in a Christian state, he created the idea that baptism is a kind of Christian circumcision—a symbol of membership in God’s kingdom. We can see where this unfortunate choice led. Zwingli was a head of state and a soldier as well. He died in battle defending the Swiss Reformation against a Catholic army.

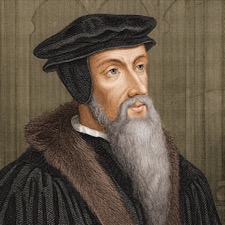

John Calvin

The greatest theologian and Bible scholar of the Reformation was John Calvin. He reluctantly headed a theocracy in Geneva, Switzerland. It was his Christian Institutes that solidified normative Reformed theology, doctrine and practice. His theological system, Calvinism, made Augustinian predestination standard in almost all of Protestantism. Even if they are not aware, most of our Christian friends are Calvinist, which explains their embracing the once-saved-always-saved doctrine.

Less well known is another Reformation which burst out, beginning from within Zwingli’s movement in Zurich. This “Radical Reformation” featured a rejection of church and state. Zwingli himself initially recognized that the only correct form of baptism is by immersion of adults, but he was unable to accept the implication of rejecting infant baptism on citizenship in his Christian state. Instead, he began to violently persecute these rebaptizers who thus became known as Anabaptists. Catholic, Zwinglian and Lutheran could not agree on much, but one thing they agreed on was that this rebellious Christ-like group must be suppressed. Catholics burned them at the stake, while Lutherans and Zwinglians drowned them. For a time, preparation for baptism of brothers and sisters was really preparation for martyrdom. Literally every one of the early leaders of this movement was martyred for their faith. Christian Europe was not yet ready to accept true Christianity with Jesus as the only head of the Church.

An Anabaptist Execution

Are we as New Testament Christians Protestants? The simple answer is no. In the International Churches of Christ, our historical roots go back to the Restoration Movement in the United States in the 1820s and 1830s. This was a back-to-the-Bible movement which rejected denominationalism, and specifically Protestant denominationalism in order to embrace Christian unity based on the essentials of the Bible alone. Leaders such as Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone recognized their debt to the great reformers, but did not accept their unbiblical creeds.

How, then, should we think about this, arguably the most important turning point in Christian history? First of all, despite their faults, and they were many, we need to honor and appreciate what Luther, Zwingli, Calvin and many lesser-known reformers did to restore Christian faith and practice. Their courage and zeal for God’s people is an inspiration. Even if we do not wholeheartedly accept their doctrines, we can give honor where honor is due and recognize that, without them, our Christian faith today would not be what it is. Their willingness to lose everything, including their very lives for the sake of the gospel is an upward call to all of us. Yet, although they did wonderful things to restore Christian practice and to restore the scripture to believers, the Protestant Reformation fell far short of reestablishing correct biblical doctrine and theology. These men restored orthopraxy (correct practice) but not orthodoxy (correct teaching). Rather than restoring New Testament teaching, they only went back to Augustine. To embrace a Calvinist/Augustinian predestination is to reject the truth that God loves all and that he “wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth.” Their rejection of biblical freedom and their relegation of Christian baptism to a mere symbol are teachings that we must reject as unbiblical and as a stumbling block to salvation.

Menno Simmons, founder of the Mennonites

Of course, there is a part of the Reformation that we can enthusiastically embrace. We can be inspired by the supernatural courage of our Anabaptist brothers and sisters. The Anabaptists were not without their faults, but neither are we. Perhaps you can get into a conversation with a Hutterite, Mennonite, Brethren or Amish friend. You would perhaps be surprised how much you have in common. However, there is one weakness of this movement that we should not embrace. Under the most extreme pressure of persecution, understandably, most of the Anabaptists chose to remove themselves from the world. They rightly rejected worldliness, but took this too far, choosing instead to isolate themselves from those who hated them. Within two or three generations, these disciples virtually stopped evangelizing the lost. As we celebrate the five hundredth anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, let us embrace the zeal, vision, and passion of all the reformers, not just the Radical Reformation, but let us take on a renewed zeal to establish the Church that Jesus died for and let us not withdraw from the world, but rather let us make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, and surely, Jesus will be with us always, to the very end of the age.

REFERENCES

Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1978)

John M. Oakes The Christian Story: Finding the Church in Church History Vol I and II (Spring, Texas, Illumination Publishers) Volume III, covering the Reformation, will be available late 2018.

John D. Woodbridge and Frank A. James III, Church History, Vol. II (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2015

Jean Henri Merle d’Abuigne, For God and His People: Ulrich Zwingli and the Swiss Reformation, trans. by Henry White (Greenville, South Carolina: BJU Press, 2000)

Spiritual and Anabaptist Writers, ed. George H. Williams and Angel M. Mergal (Philadelphia, The Westminster Press, 1957)

William R. Estep, The Anabaptist Story (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdman’s, 1996)

T. H. L. Parker, John Calvin: A Biography (London; John Knox Press, 2006

[1] Stephen J. Lawson, John Knox: Fearless Faith (Fearn, Ross-Shire, Scotland; Christian Focus Publications, 2014)