A Brief History of Christianity in China

20/05/2017 | By: Donald Downs

Whereas the history of Christianity, from its Jewish inception to its current status in the western world, is well attested to and has been copiously documented, its Chinese[1] course, for reasons we will soon discuss, is much less transparent. With multiple starts and stops, while often suffering periods of disenfranchisement and even open persecution and censorship, the Church in China has left less of a discernible historic trail than has its Western counterpart. Periods of severe oppression and governmental interdiction resulted in the destruction of many Christian artifacts, Church buildings and Christian writings that would have, had they not been destroyed, provided ample evidence for and verification of the origins and growth of Chinese Christianity.[2] Thus, these archeological losses as well as the necessity that Christians in China often had to operate, as best they could, under-the-radar of the watchful eye of a wary government, has contributed to the muted voice of the Chinese Christian record. Perhaps partly in light of this paucity of historical attestation to the activity of Christians in China, as well as to the Western bias which has long underestimated and even undervalued the genuineness of Chinese Christianity, there has been, until recently, quite a dismal outlook towards the future of Chinese Christianity.[3]

My task, in the span of a few short pages, is a monumental one - in fact nearly an impossible one. I can, by no account, provide any more than a very rudimentary glance at such an enormous topic: the history of Chinese Christianity. It would be one thing simply to note or only list the historical events of such a vast subject, it is quite another to explore in any detail the cultural factors and socio-economic conditions that guided, influenced and even occasionally interrupted this story. My hope in this short paper must be by necessity, then, a very modest one: 1) to provide a very succinct sketch of the significant eras, events and prominent leaders of Christianity in China, and, 2) to consider in compendious form only a minority of the regulating elements that affected it and a few of the salient lessons and implications of its history.

Bays, in his introduction to “A New History of Christianity in China” notes that he and other scholars have recognized that this important subject of Chinese Christianity has been a relatively understudied subject.[4] What Bays sought to do in his book was not only to document and explore what the foreign missionaries did in China but also to look more closely at the subsequent picture of the rise of the indigenous Chinese Christians as they endeavored to establish and nurture this new faith in their homeland.[5] Bays sees this process as “characterized by a persistent, overriding dynamic: the Chinese Christians were first participants, then subordinate partners of the foreign missionaries, then finally the inheritors or sole “owners” of the Chinese Church.”[6] I propose, in this paper, to provide a concise but coherent narrative that will not only acquaint the reader with the keystone elements of historical Chinese Christianity but will also point him towards some of the implications of its present outcome. It is hoped that this might not only help the reader better understand China and its Christianity, but also enhance his or her own Christian expression experience.

Some Perspective

Before we embark on our survey, let’s first consider what we are up against. Though not intended to sound like a dossier of China population stats, the following data will help quantify, and perhaps thereby impress upon the reader just how important the subject of Chinese Christianity really is. Some perspective will prove invaluable.

China’s vast population, estimated to have been fifty-nine million during the Han dynasty interregnum (the beginning of the Christian era in the West), is today about one and one-third billion… China’s Christian population is five percent of the population, which places it among the top ten Christian countries of the world, with only the United States, Brazil, Mexico, Russia and the Philippines, and Nigeria having greater numbers. Each of those countries has between fifty and ninety-five percent of their populations identified as Christians.[7]

Lodwick cites further that presently some scholars estimate the number of Christians in China at sixty-seven million. She extrapolates that, therefore, a good guess would be that throughout the entire history of Christianity in China there have been at least 100 to 200 million Christians. In 1949, when the Chinese Communist Party pronounced victory, it was estimated that there were one million Protestants and three million Catholics in China -- but by 1976, at the death of Mao Zedong, those numbers had increased to three million Protestants and three million Catholics.[8] How those numbers climbed so precipitously in such a relatively short amount of time has been amazing, and will be touched upon in the following pages of this account. However:

To further complicate the question of how many Christians there are in China today, the Chinese government puts the number around 23 million, which Western scholars think is too low. Evangelical groups, who like to point to the growth of Christianity despite the Communist government, put the number at 100 million, which most scholars think is too high.[9]

In any case, scholars are predicting that China’s number of Christians, by the year 2030, will surpass America’s count of 243 million. Tellingly, “China is on Course to Become the World’s Most Christian Nation Within Fifteen Years,” was the title of the April 19, 2015 British periodical, The Telegraph.[10]

As for the number of missionaries in China, many estimates have been made comparing the missionary numbers of the past and those of the present. Even though it is believed that there have been more missionaries to China than to anywhere else in the world, fewer records have survived about China than have from most other destinations. Part of what has so radically shaped the overall landscape of the historical narrative of Christianity in China (the persecution and repression of personal liberties), is responsible also for this dearth of information and documentation. On four separate occasions missionaries were forced to flee China: at the Boxer Uprising (1900); at the time of the Northern Expedition (1927)[11]; during the early years of WW2 (1937-41); and at the time of the Communist victory in the civil war (1949). “When fleeing for one’s life, one does not think to carry along the records on the mission.”[12] Hence, Lodwick cautions that great prudence is warranted when attempting to estimate numbers such as these.[13]

Of the major world religions to come to China, Christianity is generally held to be the second to arrive - after Buddhism and before Islam.[14] As for the adherents of each, Stark gives the following numbers based on two large and reliable surveys[15]: Buddhism 18.1%, Christian 2.7% and Islam 0.5%.[16] As for membership in the two other Chinese religions, expounded in all the comparative religion books as part of the major Chinese faiths, that of Taoism and Confucianists - only a combined 0.8% of Chinese belong to these two religions.[17] That leaves the remainder to be adherents of either the various Folk Religions or Atheists.

Six Waves of Christian Influence

As we move into an accounting of Chinese Christianity, to help digest such an expansive history, it may be helpful to conceive of seven different eras or “waves” during which the Chinese were converted to Christianity: 1.) Christian Infancy - soon after the death of Jesus and the following first few centuries, 2.) Nestorian missions - during the Tang dynasty of the 7th century, 3.) Mongol Rule and the Spread of Catholicism - during the Yuan dynasty (1206-1368), 4.) The Jesuits, Matteo Ricci, and the Spread of Catholicism - during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1636–1911) dynasties, 5.) Protestantism and Evangelicalism – missionaries, mainly from Western Europe and America, arrive and evangelize during the 19th and early 20th centuries, and 6.) Indigenous Movements – like ‘The True Jesus Church”, “The Jesus Family”, “Little Flock”, and “Local Church” which, especially after the Cultural Revolution of the 1960’s and 70’s, began to grow.[18] Also in this period would be included the state sponsored/state sanctioned churches as well as the unregistered churches. Regarding this timeline of Chinese Christianity, Bays points out that it wasn’t until after “two false starts,” and not until the 16th century that the Christian presence in China finally took root and became permanent.[19] In this present work, the “true start” of Christianity in China would then coincide with my “wave four” as, understandably, he does not take into account the Apostle Thomas’s possible evangelistic sojourn into China.

Wave One – the Apostle Thomas and Christian Infancy in China

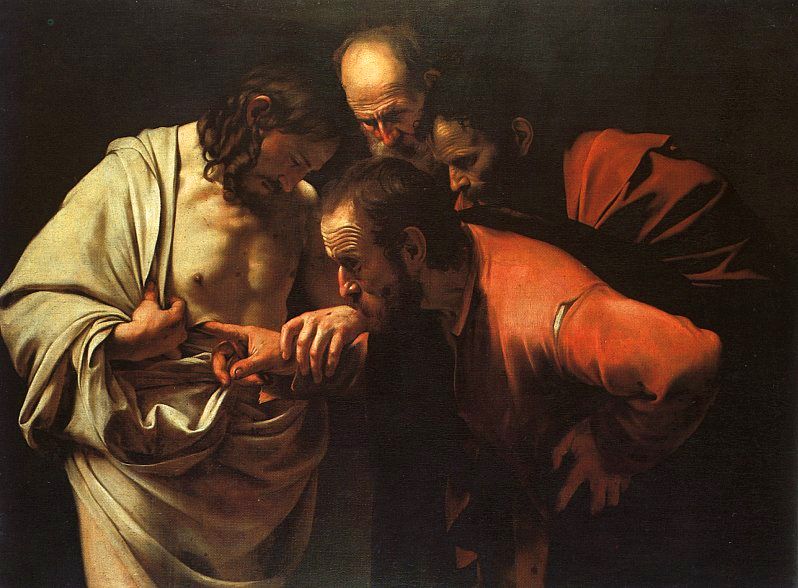

Frankly this can hardly be claimed as a definitive wave of Christianity since evidence for this is unclear and a matter of some debate, but as a possible explanation for the origin of the first Christian presence in China, it should at least be considered. Today, some historians are inclined to link the source of Christianity in China to the Apostle Thomas. Having gone to India and taken the gospel there, it is believed that he later turned to China, preaching and teaching there, until he finally returned again to India where he later died.[20] There are several indicators, though these are by no means conclusive, nor even necessarily persuasive, in support of the Thomas in China idea. First, in the 1980’s some interesting bas-relief sculptures were found on a rock face at Kongwangshan, in Jiangsu Province, near the city of Lianyungang. For many who came to China by sea this was the first port of entry and an important city in ancient times. Archaeologists have dated the sculpture to the Mingdi emperor (57-75) and the Later Han dynasty (25-220). Depicted on the sculpture are the images of three persons. Originally they were held to be Buddhists figures but over the last five to ten years this conclusion has been drawn into question. Others now claim these figures are more likely Christian and may even represent the Apostle Thomas, Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as “a variety of candidates for the third.”[21] Also the Mar Thomas Church in India, which claims to have been started by the Apostle Thomas himself, has never questioned the alleged visit of Thomas to China. Additionally, later, the great Jesuit missionary to China, Matteo Ricci, would also encounter references, albeit ambiguous ones, to the Apostle Thomas in China. Interestingly some scholars and historians of this persuasion (including authors of a 2008 book which advocated the Thomas-in-China thesis) also claim that “rather than Buddhism setting the bar for other religions, Christianity may have influenced Buddhism, which was just in its formative stages in China at the time.” [22] In the end the evidence is far from clear and certainly not persuasive, “but it is probably safe to assume that some form of Christianity made its way across the great Eurasian landmass in the early centuries of the Christian era, with the nomadic tribes who roamed along the Silk Route, stopping at the oasis towns to trade.”[23] In keeping with Jesus’ final words to his disciples, just after his miraculous resurrection and reappearance to them, to go into the entire world and proclaim his gospel, it is quite conceivable that they or their immediate successors would have indeed gone east into China with their life-changing message.

Wave Two - Nestorian Missions[24]

Here, archaeology, through its discovery of a nine-foot high ancient stele unearthed in 1623 or 1625 in Xi’an, central China, has afforded us an amazing look back in time into the early history of Christianity’s story in China. This stele contains some 1,800 Chinese characters written by a Christian monk, Jingjing, who in 781, on this ancient slab, recorded the remarkable story of an earlier Nestorian monk named, Aluoben (or Alopen).[25] Aluoben, arrived in Chang’an (now modern Xi’an) in 635 with the message of Christianity. So, here on this massive stone, was “proof positive that Christianity had been firmly established in the early Tang [dynasty] more than six hundred years before the first European emissaries came in the thirteenth century.”[26] The Tang dynasty (618-907) was “young and vigorous in 635” and ruled a much larger territory than any previous Chinese authority. Peace had been re-established between Persia and China and thus international trade along the Old Silk Road, the terminus of which was Chang’an, was flourishing. Along this route, Aluoben made his way, garbed in white robes to the emperor, carrying his sacred Christian scriptures. Once translated, and after the emperor had familiarized himself with their teachings, he issued the following edict:

The way does not have a common name and the sacred does not have a common form. Aluoben, the man of great virtue from the Da Qin Empire, came from a far land…his message is mysterious and wonderful beyond our understanding. The message is lucid and clear; the teachings will benefit all; and they shall be practiced throughout the land.[27]

As a result of the favorable disposition of Emperor Taizong towards Christianity, not only were the Old and New Testament scriptures translated into the local dialect, the first Christian Church was also founded there in 638 by this group of Nestorian monks. In all there were twenty-one Nestorian monks in China at this time.[28] Besides this stele thousands of manuscripts, including some Nestorian documents, were found in sealed grottos that effectively preserved them until their discovery in 1005. Scholars attest that these documents show “a clearly discernable Christian core” and “not any significant deterioration of the essential dogmas of Christianity.” There is, however, a “considerable admixture of Daoist and Buddhist terms and images.”[29]

Although we do not know a great deal about Tang Nestorian Christianity[30], we do know a broad outline of its fate. A massive internal rebellion nearly toppled the Tang dynasty in the 750’s such that native elements began to revive.[31] Confucianists and other cultural conservatives began to decry the foreign influence among them and, in turn, an anti-foreign-religion sentiment began to emerge. In 845 this culminated with an imperial edict limiting all foreign religion, including Christianity.[32] Emperor Wuzong (814-846) a zealous Taoist, decreed “all foreign religions be banned. The once accommodating court grew inward-looking and xenophobic.”[33] “The edict triggered a period of persecution, and, by the end of the Tang dynasty in 907, Christianity had all but disappeared from China.”[34] It would not be until the coming of the Mongols and their subsequent establishment of the Yuan dynasty that a significant presence of Christianity would reappear in China.[35]

Wave Three - Mongol Rule and the Spread of Catholicism

It was the Mongols who gave Christianity its next safe haven, at least for a time. Bays states that “just as the “pax Romana” during the first two centuries imposed sufficient security on the Mediterranean basin for the apostles to make missionary journeys far and wide, the “pax Mongolica” imposed by the Mongols made possible the first direct European Christian contacts with China.”[36] It was then that the Roman Church, in hopes of both avoiding future hostilities with the ever-advancing warring Mongols and in hopes of forming an alliance whereby they could oust the Islamic defilers of Jerusalem, began in earnest to send missionaries to China.[37] Upon their arrival, these European friars discovered among the Mongols many Nestorian Christians.[38] How is that? Prior to their arrival Nestorian Christianity had remained prevalent “in its core area of Persia and many Persian Christian merchants plied the trade routes of central Asia, where they had considerable contact with a Turko-Mongolian tribe called the Keraits.”[39] As a result, by the 13th century nearly all of the estimated 200,000 members of the Kerait tribe had converted to Nestorian Christianity. Importantly, the Keraits were an ally of the Mongol subclan, which would later produce the famous Genghis Khan (1162-1227). Genghis, through a carefully planned set of alliances, took three daughters of the Kerait royal family (each of them Christians) as wives, marrying one of them and providing wives for two of his sons with the others. It was the wife (a Kerait Christian princess) of his fourth son, who would become the mother of three emperors - one of whom in 1279 would become the founding emperor of the Yuan dynasty in China, Khubilai (1216-1294).[40]

“Under Kublai Khan, Dyophysite[41] Christians returned to the centre (sic) of power in China. After nearly three centuries in which their presence had been scarcely perceptible, they revealed themselves from generations of outward profession of other Chinese religions, which had official favour. (sic)”[42] MacCulloch goes on to describe how, in keeping with old patterns, history repeated itself when the Yuan rulers of China began to conform themselves to the “rich and ancient culture which they had seized; and, worse still, successive Yuan monarchs showed themselves steadily more incompetent to rule.”[43] Their overthrow then, by the Ming dynasty in 1368 was inevitable, though regrettable for other reasons. The Ming’s were a “fiercely xenophobic native…dynasty” and so this was a bad blow to Christianity in the empire.[44]

Prior to the Ming ascension the Mongol court was open to Christian missionaries and even turned over the administration of parts of northern China to Christian tribesmen from Central Asia. From Rome, as already mentioned, the pope also sent Franciscan and Dominican missionaries, in an effort to establish ties with Eastern Christians and to form an alliance with the Mongol empire. Additionally, Italian merchants founded Catholic communities in major trading centers; among them were two brothers from Venice, Niccolo and Maffeo Polo, who brought along Niccolo’s son, Marco.[45] It was Marco’s famous Description of the World, which he wrote after spending some sixteen years plus in China, to which we owe much of our knowledge concerning the distribution of Nestorian Christians in Yuan China.”[46] However, in spite of Nestorian Christianity’s impact on the Kerait tribes -- and, secondarily then, on the Mongols, upon the demise of the great Yuan dynasty -- once again, Christianity appeared to all but vanish in China.[47] Hence, China’s second period of Christian growth came to an end when the armies of the Ming dynasty expelled its protectors, the Mongols.

Wave Four - The Jesuits, Matteo Ricci, and the Spread of Catholicism

Here we begin to discuss the first implantation of a permanent Christian presence in China.[48] Finally, we will see Christianity begin to take root, becoming an enduring part of the Chinese religious landscape. This period will “constitute a key transition in the worldwide serial movement of the Christian faith to parts of the non-West.”[49] Even though it was Catholicism that found its start in this period, in some sense it was actually the Protestants who fueled, in a roundabout way, this influx of missionary presence in China. Back in Europe, at least in part as a response to the Protestant Reformation ignited by Martin Luther’s posting of his Ninety-five Theses, the Catholics had just recently mounted their Counter Reformation. Now, China was to become the benefactor of this movement. The Catholic Reformation facilitated an “unprecedented number of Christian missionaries coming to China in the late Ming and early Qing periods, and, more importantly, the creation within China, circa 1600-1900, of a surprising number of Christian communities; many of which proved quite resilient when the young Chinese Church was outlawed and persecuted in the eighteenth century.”[50] Here, Chinese Christianity starts to become part of the historical record, “visible in both Western and Chinese sources from 1600 onward.”[51]

It was the Jesuits that were tasked by the Papacy with this missionary calling. The Jesuits (The Society of Jesus), founded in 1540 by a zealous and inspirational young priest and theologian, Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), not only took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, but also promised, “…a special obedience to the sovereign pontiff in regard to the missions.” [52] It was Loyola’s zeal for missions that sparked a renewed European effort to bring Christianity to China. Francis Xavier, one of Loyola’s faithful disciples and a Jesuit cofounder, was assigned to the East Indies. Working first in Goa, India, he then pioneered missionary efforts into Malaysia and Japan, finally dying of disease on the small island of Shaungchuan, off the southern coast of China. It was there, frustrated by the Chinese refusal to permit permanent entry and long-term residence into Mainland China of its missionaries -- just off the coast of modern Guangzhou, that he waited in vain, and died, unable to gain passage inland.[53]

Though Xavier did not personally see his dream realized in China, notwithstanding his earlier work that spawned immensely successful evangelistic efforts in both India and Japan, it was his prodigious decade of Asian missions that opened the door for further evangelistic missions to follow in China. It was by no means, though, a wide-open door. Much challenge lay ahead for the Catholic missionaries. Up to this point their access to Mainland China was limited to Portuguese trading ports, such as Macau, on the south coast of China. Here, the traders and missionaries, unable to relocate inland, could reside year-round and were, at least, permitted travel access to Gaungzhou (Canton) for the trading season.[54] Try as they might, though, their evangelistic efforts remained coastland bound. For a while it seemed like China was a stonewall and the missionary effort of Christianity into China, a non-starter. The breakthrough did not come until 1582-1583 when the Italian Jesuit Michele Ruggieri finally gained permission to reside permanently in China. Once there he diligently set about the task of learning the Chinese language.[55] Ruggieri fortuitously chose as a partner, the now famous Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci, one of the most talented and effective missionaries in all Eastern missions’ history. Though much of the writing about Matteo appears hagiographic, that is not to say that he is not to be appreciated and admired for his hard work and great accomplishments on the mission field.[56] He was extremely successful. Ricci, the first prominent member of the Jesuits to have a place in China’s history, out of all the individual missionaries to have set foot there, is the one person whom many educated Chinese are today able to name.[57]

Monument of Matteo Ricci in Macerata, Italy

The early Jesuits who arrived in China came to a culture of which they knew very little and understood even less. There was a clash of cultures. “Traditional Chinese society was patriarchal, patrilineal, and patrilocal, and each person knew his or her place based on the traditional hierarchy of emperor to subject, father to son, elder brother to younger brother, husband to wife, and friend to friend, termed Confucian relationships by Western historians. Only the last relationship was based on equality, not bloodlines or marriage.”[58] Christianity, on the other hand, espoused a message of equality in relationships. Another challenge for the Chinese inquirers was the exclusivity that Christianity demanded. For the Chinese, it was common to practice whatever indigenous folk religion was common in a geographical region along with a syncretic blending-in of Buddhism and Taoism. Why couldn’t Christianity just be grafted onto the beliefs that they had been practicing for generations?[59]

Ricci’s approach, therefore, was to try to “tie Christianity to traditional Chinese beliefs and practices by pointing out the similarities between them.”[60] Ricci and his colleges even adopted native dress, unheard of among the missionaries of his time, in order to better relate to and gain the respect of the people. He learned rapidly and made adjustments as needed. Initially, upon his arrival he adopted the dress of a Buddhist monk (bonz), only to soon learn that the bonzes were despised among certain influential people. When this mistake was pointed out he and his fellow Jesuits accommodated, and began dressing as Confucian scholars, complete with long beards.[61] With Ricci and others at this time, a new attitude emerged among the Jesuits (which in the not so distant future would become the impetus for a great altercation, the Rites Controversy, of which we will soon speak): namely, that other world faiths might have something of value to offer and may well reflect God’s purposes, too. So, in his mind and in the practice of the Jesuits, it was worth making the effort to understand those cultures better.[62] In keeping with that spirit, Ricci put into very effective operation the policies first articulated by Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606), a fellow Jesuit, who, early on, had authority over all of Asia missions.[63] Concisely, these policies were:

· Accommodation and adaptation to Chinese culture.

· Evangelization from the top down, addressing the literate elite, even the emperor if possible.

· Indirect evangelism by means of science and technology to convince the elite of the high level of European civilization.

· Openness to and tolerance of Chinese moral values and some ritual practices.[64]

It was also Ricci who, early on, set his sights on Beijing and its imperial court, and who determined to gain permission to live there on a permanent basis. In 1602 he finally did so, the first missionary to accomplish this since the Mongols left China.[65] In the first few decades of their missions, the Jesuits overwhelmingly centered on urban missions, acquiring excellent language skills and striving to make converts from the elite class. This they did, converting the “three pillars” of the Church – Xu Guangqi (1562-1633), Li Zhizao (1565-1630) and Yang Tingyum (1562-1627) – all high degree-holders and officials of the late Ming dynasty.[66] It has been this work, focused on the missionary efforts of Beijing and its upper classes, as well as the elusive hope of an Emperor conversion that has been the focus of much, if not most, of historical scholarship on the Catholic mission.[67] Bays interjects, however, that though the attention of most scholars has remained fixed on the missionary activities at court, “the real action, and I would claim the real significance, was elsewhere.”[68] In the 1630’s, the Jesuit monopoly on China missions, having given way to the influx of other missionaries, including Spanish Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinians, and especially those arriving as newcomers towards the later part of the seventeenth century, were no longer wedded to the now century-old strategies of Valignano and Ricci.[69] By 1700, not only were the Jesuits still working at the court and elsewhere in Beijing, but a “great many Jesuits, and virtually all of the mendicant friars, were scattered across the empire creating and maintaining local rural-based Christian communities.”[70] Soon, this harvest in the rural mission field produced a deficit of clergy leadership. More and more duties were handed over to Chinese catechists and other lay leaders as helpers. To help with this need, a few pious young Chinese men were trained overseas in Seminary and returned as priests to serve the burgeoning Church.[71]

The Rites Controversy

It was during this time that one of the most commonly discussed events in Chinese Christian history took place, the “rites controversy.”[72] When the Dominicans and Franciscans (among others) arrived in China, they were alarmed at what they found to be practices among the Jesuits that were not in accord with what they viewed as appropriate missionary policy and procedure. They were particularly dismayed by and violently disagreed with the Jesuits in “their attitude to the Chinese way of life, particularly traditional rites in honor of Confucius and the family; they even publically asserted that deceased emperors were burning in hell.”[73] Complaints about the “Chinese rites” were taken as far as Rome itself when a Dominican returned there from China and launched a vehement attack on Jesuit policy in the 1640’s.[74] For the next sixty years the tide of dispute would ebb and flow, favoring first one side and then the other, based on the reports of the most recent emissaries returning from China and reporting on the issue; whether this person was sympathetic to the Jesuits or their opponents.[75] After a long struggle, successive popes condemned the rites in 1704 and 1715.[76] This proved to be a “watershed in early Sino-foreign relations, not just because of the content of the decision, but also because of the Chinese emperor’s reaction to the highly counterproductive manner in which it was conveyed to China.”[77] The papal legate dispatched from Rome conveyed the decision to the missionaries, and, as it turned out, to the emperor as well. This man, the ambassador, Touron, behaved “highhandedly towards the missionaries and disrespectfully towards the emperor.”[78]

In response, the emperor Kangxi, in 1706, decreed that all missionaries would have to undergo an examination by which it would be determined if they were in accord with the policies of Matteo Ricci. If it was determined by their responses that they were in agreement, they would be allowed to remain; all others would be immediately deported. Likewise, any who refused to take the examination were extricated as well.[79] Additionally, the emperor banished Touron to Macau, “where he languished under house arrest until he died.”[80]

Though there were a number of missionaries deported at this time, there was nothing like a wholesale removal enacted. It was not until early in the reign of Kangxi’s son, the Yongzheng emperor, in 1724, that the legal status of Christianity was rescinded. Yongsheng, upon assuming the throne, began to tighten his control over both the state and society at large, being very alert to what he perceived as possible departures from, threats to, or disloyalty towards imperial Confucian ideology. He labeled Christianity a heterodox sect, “subversive of Chinese culture and values… and renewed the expulsion of missionaries outside Beijing, calling for all of them to be taken to Guangzhou and held under detention.”[81] Christianity would remain an “illicit religion” until the 1840’s. The rites controversy “was a deeply significant setback for Western Christianity’s first major effort to understand and accommodate itself to another culture. In light of the discourteous and even contemptuous behavior of the Church in this matter it was not surprising that the Yongzheng Emperor reacted so angrily in 1724.”[82]

As a result of this proscription of Christianity in China, which would last nearly 120 years, and in combination with the concurrent dissolution of the Jesuit order by the Pope in 1773, it became increasingly difficult for the foreign missionaries to effectively service the priestly needs of the Christians in China. Consequentially, various Christian “orders developed plans to increase the number of Chinese clergy.”[83] Nonetheless, in spite of its classification as a heterodox ideology, this period was not one of uniform Christian persecution. On the other hand, just as is the case today, Christians remained vulnerable to various persecutions, arrests and other forms of harassment, even though they were not forthrightly barred from practicing their faith. Understandably, the foreign priests remained more vulnerable to arrests and deportations, as it was more difficult for them to hide their identity. All told, these factors worked together, with the net result that indigenous Chinese Christians, by necessity of these conditions, began to take greater leadership in the functioning of the Church; albeit with more assimilation of native traditions and cultural influences than was known prior.[84]

Thus by the early decades of the nineteenth century the long history of Catholic missions had resulted in a small but resilient Chinese Church, which was forced by the circumstances of its illegality to do without hands-on European management. Not surprisingly, the Chinese Christian communities made their own way forward, reconciling Chinese culture with their Christian identity as instinct and practical experience lead them.[85]

Wave Five - Protestant Missionary Efforts of the 19th and early 20th Centuries

The rites controversy, though admittedly it had an overall negative impact on the immediate success of the growth of the Church in China, may have afforded some less than obvious benefits as well. On the negative side, strong, capable, biblically educated leadership was unexpectedly ousted and ill-will (ultimately persecution and censorship) was unnecessarily created by the response and poor handling of the whole affair by the papacy. However, on the positive side, this inadvertently called upon the indigenous Chinese to step up and take more active leadership roles in the day-to-day functioning of the Church. Additionally, the commitment of those who professed Christianity was tested and even steeled as their faith met resistance and opposition. In this way, the Chinese Church began to send spiritual roots deeper into their own culture, thus helping to ensure a more lasting spiritual legacy. Scholar and historian Lars Laamann comments on the “remarkable degree to which Christianity at the grass-roots level adapted itself to Chinese traditional culture.”[86] With the periodic expulsion of the dwindling numbers of European missionaries, “Chinese Christians more or less maintained their numbers, and developed several generations of loyalty to their Catholic communities.”[87] All over China, long standing groups of Christians, their faith “rooted in well over a century of loyalty to the Church and its marks of identity – especially baptism, marriage, and funeral rites – remained standing even without their European leadership and a small but resilient Chinese Church remained, thanks to this long history of Catholic missions.”[88]

It was into this milieu that the first Protestant missionaries came, mostly European and American, over the first several decades of the nineteenth century. All of them, however, until after the Opium Wars[89] of 1839-42 (and 1856-60) and the treaties that subsequently followed, still remained limited in their activities, residing in Macau and utilizing the short trading season as an opportunity to travel and work in Guangzhou as well. Similar to the Catholic missionaries before them, like Ricci, they longed for the day when they would enjoy unrestricted access to all of China, but instead, in the first decades of the 1800’s, they remained cloistered in their small Macauan enclave.[90]

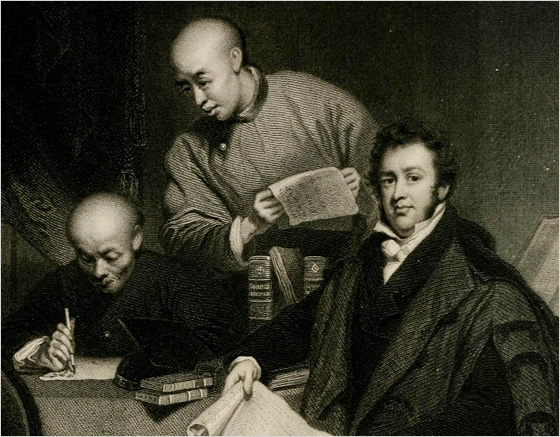

Robert Morrison

During this time and shortly thereafter, there were upwards of fifty Protestant missionaries to China. Here we will mention only a select few who played pivotal roles and had significant impact on the Protestant China mission enterprise as a whole. Scotsman Robert Morrison (1782 – 1834), sent by the London Missionary Society, arrived in Macau in 1807 and was the very first Protestant missionary to China -- and henceforth, for other good reasons as well, became one of the most well-known.

Scotsman Robert Morrison

In 1803, he began his preparations, attending the Missionary Academy at Gasport, England, and then studying under the tutelage of a Chinese language instructor for two years in London. When he arrived in China his intentions were simple, though monumental[91]; to master the Chinese language, create a dictionary, and from there to make a translation of the Scriptures that would be of value and assistance to all future missionaries.[92]In his lifetime, Morrison “was a major, if not the foremost, Sinologist of his day, and the leading interpreter of China to Western nations. He compiled, first a “systematic grammar of the Chinese, then a three-volume Chinese-English dictionary, and the Bible in Chinese” as well as numerous other publications, including an English-language newspaper in Canton.[93] Morrison himself was not especially fruitful in terms of converting the Chinese - baptizing just a few - but his seminal work paved the way for future generations and served as a prodigious contribution to the missionary effort.[94] A fitting Epitaph of Morrison carved into his gravesite marker in the Old Protestant Cemetery in Macau reads:

Sacred to the memory of Robert Morrison DD.,

The first protestant missionary to China,

Where after a service of twenty-seven years,

cheerfully spent in extending the kingdom of the blessed Redeemer

during which period he compiled and published

a dictionary of the Chinese language,

founded the Anglo Chinese College at Malacca

and for several years laboured alone on a Chinese version of

The Holy Scriptures,

which he was spared to see complete and widely circulated

among those for whom it was destined,

he sweetly slept in Jesus.

He was born at Morpeth in Northumberland

5 January 1782

Was sent to China by the London Missionary Society in 1807

Was for twenty five years Chinese translator in the employ of

The East India Company

and died in Canton 1 August 1834.

Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth

Yea saith the Spirit

that they may rest from their labours,

and their works do follow them.[95]

Peter Parker, MD

Peter Parker (1804-1888) was the first medical doctor on the China mission field. Appointed by the ecumenical American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, he arrived in 1834. Parker established the Canton Ophthalmic Hospital, China’s first modern hospital.[96] Gaining his undergraduate degree at Yale University and his Medical Degree from Yale as well, Parker was trained as an ophthalmologist in diseases of the eye. However, it became impractical, due to the overwhelming need around him, to turn away so many Chinese who came to his hospital suffering from various other maladies. As a result, over 2,000 patients were admitted, treated and preached to in his hospital during its inaugural year alone. Parker, who used Western medical techniques completely new to China, introduced Western anesthesia (in the form of sulphuric ether) to the Qing dynasty and was said to have “opened China to the gospel at the point of a lancet.”[97]

All told, before the outbreak of the Opium War of 1839, altogether from 1807 on, a “total of about fifty Protestant missionaries had been assigned to China, but only a handful had stayed for any length of time.”[98] As for actual conversions, they were very few, totaling less than one hundred for the whole Protestant effort as of 1839. Suppressed by their status as an illicit religion, hampered by the significant challenge of learning and using the Chinese language, and restricted as they were to the Macau – Guangzhou axis, the Protestant missionaries “were certain that if they could only obtain access to the interior of China, conversions would increase dramatically.”[99] Fortunately, this opportunity was soon to come.

The Opium Wars

During the first few decades of the nineteenth century, the foreign trade interests of Britain and other like-minded Western powers became pitted against the national interests of the Qing government; at the crux of the matter was the opium trade.[100] Tensions grew over the increasing amount of illegal opium flowing into China from the West. This put the missionaries of China in a bit of a moral dilemma. “They recognized the immorality of the trade, but they were certain that the war was the hand of providence opening China to the gospel.”[101] After three years of struggle between 1839 and 1842, the first Opium War ended and a diplomatic settlement was reached. The Westerners called the outcome the “treaty system,” the Chinese, the “unequal treaty system” for it was in point-of-fact an inherently biased set of arrangements forced upon China by the superior military power of the Western nations, led by the British.[102] It was also the flow of opium by ship from the West that provided these missionaries with their sole form of transportation to China. Often times they travelled aboard cargo ships, which, beneath the decks in their holds, harbored huge stores of the illegal contraband. Its transport, for most of the missionaries, provided the only possible means by which they could hope to travel to China in order to evangelize them. It is quite unfortunate, to say the least, that these early missionaries, by virtue of this issue, were bound so tightly “to the nefarious opium that addicted many Chinese and made the foreigners fabulously rich.”[103]

The East India Company iron steam ship Nemesis, commanded by Lieutenant W. H. Hall, with boats from the Sulphur, Calliope, Larne and Starling, destroying the Chinese war junks in Anson's Bay, on 7 January 1841

However, with the first Opium War ended, the treaties were enacted. The most important provisions of the first set of treaties (those enacted at the end of the first Opium War – more were to come at the conclusion of the second) were: 1) extraterritoriality (foreign citizens coming under the authority of their own consular as opposed to Chinese jurisdiction), 2) Christianity would no longer to be legally outlawed, 3) the opening up of five coastal cities for trade and residence for all foreigners as well as the right to build churches, schools, missionary residences etc. in these cities, and 4) the return of all former Church buildings to the Christians, regardless of their present status.[104] Of course this provision benefited the Catholics only as there were no Protestants, and thus no Protestant properties, in China prior to the entry of these first Protestant missionaries at the turn of the nineteenth century. With the opening of these five “treaty port” cities of Guangzhou (Canton), Xiamen (Amoy), Fuzhou (Foochow), Ningbo, and Shanghai, as well as the ceding of Hong Kong in perpetuity to Britain as a crown colony, the protestant missionaries now enjoyed a wider scope for their activities. New denominations appeared on the list of Protestant missionary societies, most of them moving their headquarters to Shanghai.[105] The missionaries now began preaching to the urban populations, training helpers and Chinese evangelists as well as engaging in extensive written communications, chronicling their efforts and results.”[106] Still, though, the missionaries remained stymied in their efforts to move beyond these few cities.[107]

The Taiping Rebellion

China, the greatest Asian empire, ruled by the Qing dynasty at this time, seemed only to barely escape destruction and collapse at the hands of the interfering Western powers. “The arrival of Christianity and interference by European powers identified with the Christian faith contributed to a catastrophic rebellion, and almost a century would follow before Churches could free themselves from association with imperial humiliation. The Protestant penetration into China, riding on the coattails of Western colonialization, was made possible in large part by the treaties made with the European powers as they encroached on Chinese sovereignty without chagrin.[108] “It was a contradictory mixture of popular anger and fascination with Western culture that fueled the Taiping rebellion, which broke out in 1850.”[109]

Its first ideologue and leader, Hong Xiuquan, having failed his civil service entrance exams (indisputably essential in China for upward mobility), in a state of high anxiety and stress began reading Christian books, encouraged by a young American missionary.[110] Soon Xiuquan, convinced by visions that he had been chosen by God, as His son and Jesus’ brother, for great leadership, amassed a tremendous following among the disenfranchised of southwest China. His movement, fed by an incendiary combination of “nostalgia for the Ming dynasty, traditional rebellious zeal to end corruption,” and a concoction of various Christian concepts, especially those of an apocalyptic nature, united his followers with consequential results.[111] He eventually created his Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace creating an entire governmental structure with a sizeable army. Before it ended, the Taiping rebels controlled fifteen of the eighteen provinces of China below the Great Wall.[112] The rebellion eventually took over most of south central China, ruling over some 30 million people, and wreaked catastrophic results before it was finally subdued when imperial troops led by European officers stopped him at Shanghai.[113] It proved to be the most destructive civil war in all of history, dwarfing the contemporary American Civil War and nearly outstripping the mayhem caused by the Second World War a century later.[114] The Taiping Rebellion finally concluded having caused an estimated 20 to 30 million deaths, most of them civilians.[115]

Even while the Taiping war raged into the late 1850’s, the Qing court was confronted with yet another military action, this time by a British-French consortium. What seemed like a natural course at the time would be viewed now with disdain and rightly labeled “imperialism” with all the negative connotations conjured up by the term today. The intervening Occidental powers hoped here to settle once and for all the issues left unsolved to their satisfaction by the treaties of 1842-1844. This war, which lasted from 1856-1860, resulted once again in a round of unequal treaties favoring the Western victors. In the signing of these treaties the missionaries finally gained more of the freedoms they had so desperately wanted and needed to help propagate their evangelistic efforts.[116] The treaties contained provisions giving the missionaries the right to work in China, to own property and to travel beyond the treaty ports.[117] As a result the missionary societies escalated their efforts with a corresponding increase in both missionaries and converts. “By 1893 there were 1,243 Western Protestant missionaries [in China] with a claimed total of 55,093 active Chinese converts.”[118] Predominantly, Great Britain and America fueled the missionary efforts of the Protestants in China. In 1877 there was a combined twenty-five different denominations with missionaries there, but by 1910 that number had risen to forty-four American and nineteen British. A total of sixty-three denominations were then active in sending and supporting missionaries to China.[119]

During this time, from 1860 through the end of the nineteenth century, the young Chinese Protestant Church was putting down roots of community that constituted a solid foundation for the future. This period was marked by rapid growth of the foreign missionary establishment among Protestants, during which time they were becoming a more diverse spectrum of missionary establishments in China. “During these decades, several Protestant urban congregations served by Chinese pastors developed the capacity to support themselves financially and to operate on their own, without being under close missionary supervision. In fact, during these years Protestant Christianity became a true Sino-foreign endeavor, though the role of the Chinese was often in the shadows.”[120] Though Stark puts the number of Protestant converts by 1893 at approximately fifty-five thousand, Bays estimates that by 1900 there were one hundred thousand. There was growth among the Catholics as well, but due to their inherent allegiance to a foreign power, Rome, and the necessity of more strict clergy involvement, there were fewer cases of real Chinese and foreign cooperation. The airtight control of the Catholic Church also denied the Priests much of a real voice in managing their local affairs; despite the fact that their role in the growing Church was essential.[121]

John Talmage, Hudson Taylor and the Chinese Inland Mission

There was an immediate reaction from the west to the changes brought about by the latest treaties of 1858-1860, wherein the entire country was opened up to foreign travel as well as to the acquisition of property and subsequent erection of buildings upon these leased or owned lands. “Indeed in the years after 1860 all over China the number of Protestant Missionaries in China exploded, from barely 100 in 1860 to almost 3500 in 1905. It was an astounding increase, considering that it had taken more than 50 years from Morrison’s travel there in 1807 for the numbers to reach 100.”[122] The massive increase in Protestant missions of this time was due also, in great part, to the increasing efficiency and professionalism of the missionary societies of Europe and North America.[123] Even as the majority of missionaries continued to operate under more formalized and structured missionary society entities, there were those that took the opposite route.

JohnTalmage (1819-1892), an American Reformed Minister, stationed in the British occupied city of Amoy, sought to learn from the mistakes of earlier Catholic successes and failures by implementing strategy whereby he determined to make foreign missionaries redundant. He and a few other like-minded colleagues created one of the earliest fully fledged Chinese churches and erected the very first Protestant Church building in all of China. Beginning from Amoy, one of the treaty ports opened up by the Nanjing Treaty of 1847, “soon his congregations, fortified by a sensible amalgamation of American and English Presbyterian foundations, were electing Chinese elders in classic Presbyterian style, struggling towards self-support and taking on themselves the founding of new congregations.” [124]

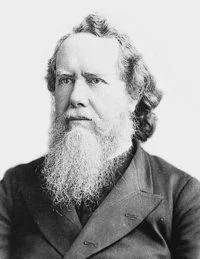

Talmage’s strategy was put into effect on a grander and much more publicized scale by the Englishman, Hudson Taylor (1832-1905). Early on, Taylor, after thinking through various issues regarding missions-strategy, decided that a self-supporting entity, which would be beholden to no institutional powers or preferences, would best serve the purposes of evangelization among the Chinese. Subsequently he initiated a “faith based” mission in which all support would be garnered organically. Arriving earlier in Shanghai, in 1854, under the auspices of the Chinese Evangelization Society, he had experienced issues, concerns and setbacks that he was determined to circumvent in the future. After a brief return to England, he soon embarked again for China, this time as part of the largest party of missionaries ever sent to China. He returned this time as the founder and the first Chinese missionary of the China Inland Mission.[125] The CIM’s practices were both innovative and sometimes controversial:[126]

Hudson Taylor

· The CIM “sought no support except that of God himself,” all confidence was placed in divine provision. He was determined never to divert funds from other missions.

· Taylor appointed laypersons, not clergy, as missionaries. In fact, even from the outset when he and twenty-one others arrived as the first contingency of the CIM, not one of them was ordained clergy. He did not even require any college training among his candidates.

· Taylor adopted a non-urban strategy and so they developed relatively few supporting entities such as schools, hospitals, etc. Those schools that were developed were to educate their children in China and not send them back to Europe for their education, as was the universal norm.

· In order to more effectively identify with the local peoples, the CIM was the first mission to adopt the practice of wearing traditional Chinese garb as a matter of policy.

· The CIM was among the first missionary groups to allow large numbers of women to serve as missionaries – even to work in the countryside without male accompaniment. Many at the time saw this as scandalous.

· “The power structure of the CIM evolved into the primacy of a China-based “council” or headquarters based in Shanghai, not in London or elsewhere in the West.”[127]

Taylor was charismatic and effective in his role as leader of the CIM. Back home in England he solicited the masses for support of his grand mission in China. Starting with just his original 22 missionaries in 1866, the CIM grew to 322 in 1888, and to 825 in 1905. By then the CIM had grown to be the largest missionary society, almost three times larger than the British Church Missionary Society (CMS), the next largest group.[128] Taylor’s success was additionally elevated by the highly publicized recruitment of the “Cambridge Seven,” seven aristocratic young Cambridge graduates. This event, “one of the grand heroic gestures in nineteenth-century missions, catapulted the CIM from comparative obscurity to an almost embarrassing prominence.”[129] Taylor also worked closely with the YMCA and YWCA, utilizing as well, significant publicity wrought by his effective publications, prime among them: the “China’s Millions.” All of this helped to fuel the stunning growth and compelling impact of the China Inland Mission.[130]

The Boxer Uprising

Even as the colonializational treaties opened doors for the spread of Christianity, and as the growing influx of more missionaries into China fueled the growth of the Church and its further integration into the social structure of the Chinese nation, so, too, did the imperialistic persona of the Western national and Church powers cast an ill shadow on the good work that was being accomplished. Bays elucidates the matter well:

In the late 1890’s, even as 1) some degree of “Christian influence” was seeping in through the walls of the imperial palace in Beijing to coalesce around the emperor; 2) newly politicized, urbanized elites became alarmed at China’s weaknesses and vulnerability; and 3) those same elites took the unprecedented steps of organizing themselves and expressing opinions on government policy – two other results came into being as a result of these developments. These were the seeds of modern nationalism…identified in the activism of these elites, and a related phenomenon, the emergence of a modern public opinion.[131]

Soon, nationalistic fever, as well as the smoldering frustration of repression among the Chinese, fomented into an uprising that came to be known as the Boxer Rebellion or the Boxer Uprising.[132] By the end of the nineteenth century the Western powers, via the Opium Wars, as well as Japan by way of the Sino-Japanese war, had enacted millions of casualties on the Chinese. In the late 1890’s this secret group, the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists (the Boxers), had begun to carry out sporadic but regular attacks on foreigners and on Chinese Christians.[133] In 1898-1900 Christianity, foreign missionaries and Chinese converts alike became targets of mass and official violence on a scale that dwarfed that of the “Tianjin Massacre” just twenty years earlier.[134] What began as seemingly low-level activities of Boxer violence perpetrated upon both missionaries and Chinese Christians escalated in the spring of 1890 culminating in the now famous siege of the Legation Quarter in Beijing not far from the Forbidden City.[135]

Four hundred and nine poorly armed American and European embassy guards barricaded themselves in behind the Embassy walls. It was with the Empress Dowager, Cixi’s, support that imperial military forces joined the siege where, for forty-five days, the embassy guards stood firm against the onslaught of thousands of Boxers and thousands of imperial Chinese troops. The siege was broken by the arrival of a large, eight-nation expeditionary force in August of 1900.

Outside of Beijing, the Boxers killed all foreigners and Chinese Christians within their reach. Unfortunately, by the end of the uprising, some 30,000 Chinese Christians were killed as well as 47 Catholic priests and nuns, 136 Protestant missionaries and 53 of their children. Some of these were raped before death and were killed in gruesome manners. After its suppression, the Chinese were again forced to sign a treaty. In September 1901, the Protocol of Peking (Boxer Protocol), in which major reparations were stipulated, was affirmed in writing.[136]

The Boxer Rebellion is quite well known; the enterprise documented in lucid detail, as are the atrocities committed against the Western missionaries and Chinese Christians through its activities. What is often left out, or visited with little detail, is the ensuing sustained occupation of the foreign troops which remained in China for well over a year, as well as the vengeful retribution they enacted, making raids hundreds of miles away, sometimes destroying villages and summarily executing as many as a thousand Boxers and/or their alleged sympathizers. “However, much to the surprise of most observers, within two years of the Boxer events a new spirit of enthusiasm for reform was gripping the remodeled Manchu government…the elite class and officialdom was showing more respect for missionaries and Christian institutions than had ever been the case before.”[137] At last, felt the missionaries and Chinese Christians; China might be turning towards Christianity. In the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising tragedy we see the “beginnings of China’s “golden age” of Christian expansion and self-confidence.”[138]

Russian cannons firing at Beijing gates during the night. August, 14, 1900

Ironically, the great tragedy of the Boxer Uprising ushered in a period of more than two decades during which time the foreign mission enterprise in China, as well as the Chinese Christian communities at large, seemed to flourish. In fact, when the Republic of China came into power after the toppling of the Qing dynasty in 1912, China had its first Christian (Protestant) provisional president; Sun Yat-sen.[139] Measures of raw numbers similarly document the vitality of the Protestant missions of this period. “Protestant growth between 1900 and 1915 was impressive by all indices.”[140] The number of foreign missionaries increased from 3500 in 1905 and 5500 in 1915 to 8000 in the 1920’s. The numbers of Protestants grew as well: 100,000 in 1900, with 270,000 communicants (330,000 baptized) in 1915 and 500,000 in the 1920’s – “before the storm of mass nationalism hit.”[141] Sadly though, this storm of mass nationalism was soon to come.

Before we go on to look at the cataclysmic changes to come, wrought by the resurgence of Chinese nationalism, a comment is in order about the changing nature of the Chinese Church, which began to surface during these years of relatively unrestricted and unhindered growth. With this growth came new developments. During this time, the Chinese Protestant community was coming into its own, and developing more of a sense of autonomy, moving more and more towards independence from its foreign missionary leadership.[142] It was during this time too, reflective of this growing independence (if not divergence) that the last of the great missionary conferences, in which all groups were represented, in spite of their doctrinal differences, was to occur. Regrettably, this unity did not last much past the end of World War I. “The broadened spectrum of Christianities now available could not easily co-exist. The old consensus was already disintegrating even as preparations were being made…for the National Christians Conference of 1920.”[143] Doctrinal differences began to emerge such that genuine collaboration among the churches and among the missionary societies became increasingly difficult. Frankly, on some fronts, what began to transpire in China was representative of what would happen worldwide among Christians everywhere – the emergence of the “Fundamentalist-Modernist” controversy.[144] The divergence of theologies regarding this issue, as well as others to come, would lead in various ways to a greater diversification of the Chinese Church.

Wave Six – The Rise of Indigenous Movements

The True Jesus Church, The Jesus Family, Little Flock and Local Church

It was only a matter of time, and it was in fact the missionaries’ ultimate goal, before Christianity’s roots would mature and sprout new growth: growth native to the Chinese people. After 1927 and before 1949, when the Communists were purged from China and the Chinese Communists Party (CCP) driven underground by the authority of the Nationalists, the government adopted a much less radical attitude towards foreigners and Christianity than would be the case upon their coming ascension to power.[145] With the CCP out of the way and out of the field of vision, conditions for the operation of the missionaries were much less onerous. Most of the foreign missionaries who had fled as the Nationalist party turned on the Communist, effectively ousting them, fled the country in 1926-1927 in the wake of the conflict, unsure of what the final outcome might mean. Though many returned in 1928 -1929, only about 600,000 of the previous 800,000 did so. “They did have to abide by the new Guomindang (of Nationalist) government requirement that the chief officer of every Christian school must be Chinese, that religious instruction be optional for students, and that there be Chinese patriotic political instruction under the banner of Sun Yat-sen’s “three people’s principles. But missionaries still had extraterritorial privileges, and many government officials (including Sun Yat-sen himself who was baptized a Protestant Christian in 1930) were Christians, which facilitated the work of both missionaries and Chinese.”[146]

In the mid 1930’s, foreign and Chinese Christians were arrayed along a wide spectrum of varying types of missions, churches, Christian organizations and movements. On one end of the spectrum were the Church of Christ in China (CCC) and the National Christian Council (NCC) where nationalism and social conscience served as core motivators; further along the spectrum were the more distinctly conservative elements of mission groups and churches. This included the Chinese Inland Mission (CIM) of Hudson Taylor as well as other groups including Presbyterians, Lutherans, Methodists, the Church of the Nazarene and the Assemblies of God. And finally, there were many “one person” faith missions scattered among the others, all of these groups stressing more the conversion and regeneration of the individual than that of society at large.[147] Finally, along the opposite end of the gambit from that of the CCC and NCC, were scores of new churches, “wholly independent and without any foreign leadership whatsoever, although each of the founders of these movements was influenced by foreign Christians at times early in its development.”[148] These Churches are not only interesting to examine, they have also become an important subject of discussion among scholars investigating the Sino-Christian field of studies.[149] Following, I will look at three of these: The True Jesus Church, The Jesus Family and the Little Flock and Local Church.

The True Jesus Church[150]

The True Jesus Church had its beginnings when, in 1916, founder Wei Enbo in Zhengding, Hebei Province, had hands laid on him by a Pentecostal preacher in order to heal his tuberculosis. Healed, as he thought, Wei became an impassioned Pentecostal with claims that he had received the Holy Spirit and the gift of Tongues. Soon thereafter he was “led by the Spirit” to a river outside Beijing where he heard the voice of God and was especially chosen and empowered to “kill the demons” (which he forthright did, right there at the river, chasing and destroying the demons in some otherworldly confrontation) and “correct” the Church, meaning all Christian churches.[151] Embarking on a 39-day fast, during which he encountered Jesus and the twelve Apostles and received his new name, Paul, Wei emerged ready to do God’s bidding. Soon he and his followers were visiting mission churches in and around Beijing, denouncing Western Christianity, and calling parishioners out of those churches.

The True Jesus Church (TJC) “doctrines and practices are a unique eclectic combination of sabbatarianism…Pentecostalism…and a kind of Jesus only Unitarianism… all of this packaged in a radical egalitarianism.”[152] Additionally, Church workers were not to receive pay; worship services were to have no time constraint limits and all members must be given free rein to speak, pray and otherwise participate in the services.

Unfortunately for Wie, he was not cured of his Tuberculosis, and so died of its complications in October 1919. His Church, though, continued to grow and even flourish. By the time of the Sino-Japanese war, the TJC was likely the second largest Protestant Church in China – second only to the Christian Church of China (CCC). It is still thriving today.

The Jesus Family[153]

“The Jesus family was a product of the North China Plain in Shandong Province and its alternating cycle of flood and drought.”[154] This was a land of peasantry, a people who were constantly besieged by both the ravages of their environment as well as the lawlessness of the tens of thousands of bandits and soldiers who roamed and frequented their lands. “A partial remedy in the eyes of many was the formation of mutual-aid societies for extending credit to farmers, marketing crops or local products, and generally filling in the gaps or weaknesses in the community’s solidarity. It was in this milieu that the Jesus Family was formed.” It was a “sectarian mutual-aid community independent of mission Christianity and bound together by Pentecostalism and an ascetic pursuit of end-time Salvationism.”[155]

The founder of the Jesus Family (JF), Jing Dianying (1890-1957), was himself not a peasant but was from a well-educated, fairly wealthy family. Bringing together a mix of experiences and teachings from Methodism, Confucian ethics, Daoist mysticism and Millenarianism, in 1921 he started a Christian silk-making cooperative, from whence would come The True Jesus Family, the name this group would soon adopt, in 1927. All who joined the JF were to give up and share all their possessions with the community, partake in productive work, and engage several times daily in periods of prayer and worship. Individual ecstatic experiences were not unusual and in fact were desired and prized among the participants. Soon more groups similar to this one sprouted up; each with a “family head” leader who exercised the same extensive control over its members as did Dianying. Though the JF had nowhere near the number of adherents as did the TJC, its egalitarian culture was attractive to many, and provided a life of simple subsistence, along with an intense religious experience for its members.

Watchman Nee

Born in 1903, Ni Shu-Tsu was the son of a customs official and the grandson of a “gifted Anglican preacher.”[156] While attending the Anglican Trinity College in Fuzhou, Nee was converted during a revival meeting at just seventeen years old. Only five years later, in 1925, he would change his name to Ni To-sheng, or Bell-ringer, translated into English as Watchman Nee, and found his first Church in Sitiawan.[157] The following year, he opened his second Church and in 1928 he built a three-thousand-seat assembly hall in the center of Shanghai. While there in Shanghai, Nee gave himself to extensive reading of the mystic, Jessie Penn-Lewis, and subsequently produced the lengthiest book he ever authored, the three-volume, The Spiritual Man.

Watchman Nee, founder of 200 churches

Just as most other independent Christian leaders were learning about and adopting Pentecostalism, Nee investigated it as well, “but chose a slightly different path to spiritual transcendence.”[158] Nee’s theology centered on “the mystery of the cross” or “the truth of the cross” - that is, “the realization for the Christian that, ‘I am dead with Christ,’ enabling the believer to live in victory over the world’s evils.”[159] Additionally, Nee enumerated an elaborate theology of Millenarian flavor, of an end-time cataclysm. Nee’s congregants were mostly of middle- and upper-class strata, and more urban than rural. He strongly rejected denominationalism and was adamant that he and his followers adopt no sectarian name. He refused to allow his followers to call themselves by any particular name. His emphasis on the “local Church” or ‘one Church in each city” lead to his groups being referred to as the Little Flock or the Local Church. By 1933, Nee claimed to have more than one hundred Churches spread all across China.

When the communists rose to power, Nee felt that the Little Flock was safe in that it was an entirely Chinese entity and had never had any foreign missionary element. Though that was true, it did not protect Nee from the concerns of the Communists, who, to a great degree, were uneasy, among other things, primarily about his visibility and popularity. In April 1952, after being arrested and charged with spying, he was incarcerated in a re-education camp only to, later, in 1956, be further charged with more serious crimes. Ultimately, Nee was tortured and finally died in prison, his Little Flock driven underground after 1949. Stark asks, “But even though driven underground, the Little Flock Movement survived and grew. How? They kept a very low profile and organized cell groups and home meetings at the grassroots level, which later formed the backbone of the Chinese House Church Movements and sowed the seeds of religious revival.”[160]

A Brief Chronology

Before we move into the next step of our coverage of the history of Christianity in China, specifically the precipitous rise of Nationalism, a brief review of secular Chinese history may help the reader to gather context for a more coherent grasp of the events that follow. It may help the reader to occasionally reference this list as he reads on through the remainder of this paper. Here is a basic bullet list review:[161]

· 1912 - Demise of the Qing, the last of the Imperial dynasties.

· 1912 - Republic of China (ROC), a Nationalist party comes to power in Nanjing, ruling until 1949. Nationalists. In 1949 the ROC took control of Taiwan, which is now the modern-day ROC.

· 1921 – Founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as both a political party and a revolutionary movement in Shanghai, China.

· 1924 – the CCP joins with the Nationalist Party.

· 1927 – Nationalist party (ROC) turns violently against the CCP, which is driven underground.

· 1949 – CCP establishes the People’s Republic of China (PRC) formed after a 23-year civil war fought against the ROC (1927-1949). This communist government enacted sweeping changes in the socio-political order. A strong sense of independence and nationalism was fostered. Ties were established between state and Church in order for existing churches to remain active.

· 1954 – Organized in 1951 but granted official government sanction in 1954, The Three Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) announced to help ensure national loyalty and to help make the Church distinctly Chinese. Self-governance, self-support and self-propagation were the goals.

· 1966 - 1976 - The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution occurred. This was a socio-political movement enacted by Chairman Mao of the Communist party, aimed at purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society and re-imposing Maoist thought as the dominant ideology. Between 1966 and 1968, the destruction of the Four Olds (Old Custom, Old Culture, Old Habits and Old Ideas) took place. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (Red Army) targeted religious and educational institutions. Priests, nuns, monks, authors, professors and artists, as well as the educated elite in general, were persecuted by destruction of property, pubic humiliations, physical violence and even death.

· 1980 - After the chaos and destruction wrought by the Cultural Revolution, in 1980, the China Christian Council (CCC), an umbrella organization for all Chinese Protestant Churches, was established to help Chinese Churches by providing oversight as well as resources such as Bibles and other religious literature.

· 1982 - the Chinese Communist Party issued Document 19, a detailed description and explanation of government religious policy, essentially outlining that religious practices would be permitted, although subject to the oversight and regulation of the party-state.

The May Fourth Movement

Tiananmen Square and the rise of Nationalism

Opposition to Christianity in China, at varying levels over the centuries, has been a staple part of the Christian existence there. Many traditional Chinese had protested Christianity as a foreign faith and one unsuited to Chinese culture. Then, beginning with the student protest movement that erupted in Beijing, on May 4, 1919, increasingly, the most modernized Chinese began to attack Christianity and its missionaries on multiple grounds.[162] Though the immediate concerns that prompted the protests -- that of the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, in which Japan received territories back from Germany that were supposed to be returned to China -- did not directly involve the Christians or the missionaries, it did give occasion for Chinese nationalism to vent itself more forcefully than any could have expected. “There was little or no indication that the rippling effects of those precipitating events would soon constitute a mortal challenge for the Protestant movement in China.”[163] There was, however, a growing tide of resentment that, within a year, would crystallize and “take dead aim at Christianity and its institutions, its believers and especially the missionary movement.”[164]

This movement, which began in Tiananmen Square with more than 3,000 students from Peking University shouting slogans of protest and defiance and even burning down a Chinese official’s residence, soon spread to students all across China. Additionally, these mass urban protests and demonstrations went well beyond just student involvement; urban merchants, white collar workers and factory workers revealed a simmering resentment through their involvement as well. Two issues have been recognized as the impetus for the intense opposition to, and subsequent persecution of Christianity at this time, 1) China’s intellectuals perceived Christianity as crass superstition “with outlandish beliefs in a virgin birth, raising of the dead”, etc. and 2) the charge against the West and its missionaries of cultural imperialism or cultural aggression.[165]

The People’s Republic of China – A Communist Regime

“Early leaders in China’s Communist Party, including Mao Zedong, acknowledged the May Fourth Movement as leading directly to the founding of the party in 1921. As Marxists, the Communist leaders regarded all religion as an opium of the people, and that went double for Christianity since it was a foreign intruder.”[166] Before the Chinese Communist Party was to overcome the Nationalist party in the Chinese Civil War and declare itself victor, and China the new People’s Republic of China, the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 diverted the attention, focus and resources of both factions.[167] Together they turned their attention towards defeating their foreign aggressor.

During this time, as Japanese forces overran segments of China, the missionaries in their path, in the areas of Japanese occupation, suffered great loss. Missionary stations were destroyed, forcing many missionaries to go home. Additionally, once Pearl Harbor was bombed and America entered the war, all American and British missionaries were deemed foreign enemies and were thus placed, more than a thousand of them, into prison camps. It was in one such camp that the famous Olympian runner-come-missionary, Eric Liddell, died.[168] Once World War II ended, the Civil War in China recommenced. Ultimately, in 1949 the Chinese Communist Party won victory over the Nationalists and China was declared the People’s Republic of China – and was now under a communist regime.

Initially the communist regime seemed not to hinder the exit from the country of those who chose to do so, as many hastily did in light of the new state of affairs. However, in part because of the entry of China into the Korean War in 1950, foreign missionaries began to be arrested under the suspicion of espionage. Incidents arose in which some missionary families were given long prison sentences and others were even killed. The Catholics, because they acknowledged allegiance to the Pope, aroused the greatest suspicion and therefore the most fervent hostility. Even before they took over control of China, in areas where they had previously exercised dominion, the communists had killed ninety-six Catholic missionaries between August 1945 and April 1948.[169] Additionally, Catholic Church properties were seized and most of their churches were forcibly closed. “By 1951, most of the remaining missionaries, both Catholic and Protestant, were placed under house arrest, and by the end of 1953, all of them had been expelled.[170] Though this was a lamentable turn of events in the history of Chinese Christianity, much in the same way that the persecution suffered by the First Century Church spurred its growth (not to put it too blithely) so too these persecutions may have been just what the China Church needed at this time as well. As Stark says, “In terms of numbers, the story of Christianity in China really begins after the last missionaries left in 1953. Now, sixty years later, despite a period of intense government persecution and repression, millions of Chinese have been converted.”[171]

Creation of The TSPM and CCC

Persecution and Re-Emergence of (Unregistered) Churches

1951 - The Three-Self Patriotic Movement